When my father told me he hit my mother only once in twenty-three years of marriage, I didn’t even bother replying. A long time had passed since I had challenged any of his stories, with their fabricated events, dates, and details. When I was a boy, I always saw him as a liar and his lies embarrassed me, as if they were my own. Now, as an adult, it didn’t even seem to me like he was lying. He truly believed his words could recreate facts according to his desires or regrets.

A few days later, though, his punctilious assertion resurfaced in my thoughts. Initially I felt unease, then growing anger, and finally the desire to pick up the phone and yell into it, “Really? Only once? And all those times I remember seeing you hit her, right up until she started dying, what were they? Love taps?”

Of course I didn’t call. Although I had been playing the role of devoted son for decades, I had also managed to hand him a fair number of disappointments. And besides, it was pointless to attack him directly. His jaw would’ve dropped the way it always did whenever something unexpected happened and, in that mild tone of voice he always used when he disagreed with us children, he’d start to list with great suffering—and via long-distance—all the irrefutable instances of cruelty that he had not inflicted on my mother but she on him. “What difference does it make if he continues to invent things?” I asked myself.

Actually I realized that it changed a lot. To begin with, I changed, and in a way I didn’t like. It felt, for example, like I was losing the ability to measure my words, an art that I had proudly mastered as a teenager. Even the question I had considered yelling at him (“And all those times I remember seeing you hit her, right up until she started dying, what were they? Love taps?”) was poorly calibrated. When I tried writing it out, I was struck by its crass and impudent style. I seemed to be making exaggerated claims not unlike those of my father. It was as if I wanted to reproach and shout at him for slapping and hitting my mother even as she lay on her death bed, punching her with the expertise of the gifted boxer he said he had been at the age of fifteen, over at the Belfiore gym on Corso Garibaldi.

This was a clear sign that all it took was the slightest hint of my age-old anger and fear to make me lose my poise and erase all the distance I had managed to put between us while growing up. If I actually spoke those impulsive words, it would be like allowing my worst dreams to blend with his lies. It’d be like giving him credence, agreeing to see him the way he chose to represent himself, as someone you don’t mess around with, which was what he learned as a kid from European champion Bruno Frattini, who egged him on in the ring, and encouraged him with a smile. “Go on and hit me, Federí! Hit me! Kick me!” What a champ. He had taught him that you dominate fear by striking first and striking hard, a principle he never forgot. And since that time, whenever the occasion arose and without the least preamble, he’d size up his victim and proceed to bash the bones of anyone who tried to boss him around.

To be good enough, he started training on Saturdays and Sundays at the Giulio Luzi sports club. “Giulio Luzi? Not the Belfiore?” I’d ask with a hint of spite. “Giulio Luzi, Belfiore, whatever, they’re all the same,” he’d reply gruffly. And then he went on: the person responsible for introducing him into the sports club for the first time was none other than Neapolitan featherweight champion Raffaele Sacco, who happened to be walking down the street while he was fighting tooth and nail with a gang from the neighborhood near the railroad station that used to regularly throw rocks at him and his brother Antonio. Sacco, who was eighteen at the time, stepped into the fray. He threw a couple of punches in those sonofabitches’ faces and then, after praising Federí for his courage, conducted him to the Giulio Luzi or the Belfiore or whatever the hell you want to call it.

That was where my father started boxing, and not just with Raffaele Sacco and Bruno Frattini but also with the latter’s protégé, Michele Palermo, the massive Centobelli, and tiny Rojo, champions one and all. He made swift progress. A kid named Tammaro learned it the hard way when he harassed him as he was walking home from school with his brother Antonio. “You? A boxer? What a joke, Federí!” he taunted him. Without a word, my father knocked him flat with a left hook to the chin. Then he turned to a friend of Tammaro’s who stood there paralyzed with terror and said, “When he wakes up, tell the bastard that next time I’m going to kick his ass, not just his face.”

His ass. I was frightened by those stories. I was disturbed, too, because I had no idea how to protect my own brother from the kids who threw rocks at us, the way he had done for his brother. I was worried about heading out into the world without knowing how to land a punch. And I felt anxiety, even later on as an adult, when I saw how well my father could do the voices of violence, the posturing, the gestures, kicking and punching the air.

In the meantime, he seemed to derive enormous pleasure from his ferocity, from the way he knew how to deploy it. He used to tell me those stories to incite my admiration. Now and then he succeeded, but for the most part I felt a combination of distress and fear, which stayed with me longer. A case in point: the two shoe-shine boys on Via Milano, in Vasto, at 7 p.m. on a summer evening. My father, seventeen at the time, and his brother Antonio, fifteen, were on their way back from the gym on Corso Garibaldi. Suddenly it started to rain. The two boys—it was Saturday and they were wearing their fascist uniforms, something my father emphasized proudly, even decades later, in the belief that his outfit made him look sharp and terribly manly—ran for cover under the porticoes of the Teatro Apollo, where there was already a cluster of other people, including the two shoe-shine boys. There was clamoring, heavy rain, the smell of wet dust. When the shoe-shine boys caught sight of them, they sneered cruelly. “Those two ugly sonofabitches made it rain,” one of them said loudly to the other. Their brutish words offended the boys, their mother, their father, maybe even their ominous black shirts. Without thinking twice, my father reached over and, with his left hand, grabbed the collar of the shoe-shine boy who had spoken those words, even though he was big, tough, and around thirty, and planted an uppercut on that Neanderthal’s foul mouth—Neanderthal he called him, to show how primitive he was—knocking out his two front teeth. Thwack. He punched him so hard that one of the man’s broken teeth—and at this point in the story, he’d wave his index finger in front of me to show me a scar that I couldn’t actually see but to appease him I said yes, Papà, I see it—got wedged into the flesh of his finger. He had to flick his hand hard to make it fall out.

Whenever he told that story, he always flicked his hand hard, as if the fragment of tooth was still stuck in it. I’d stare at him in horrified devotion: lean and lanky, he had a long face, high forehead, and a slender, elegant nose with delicate nostrils, a nose that definitely didn’t look as if it belonged to a skilled boxer. He always came home from work furious, as if he had just knocked out Tammaro or the shoe-shine boy; always the victim of some urgent, dramatic situation; always ready, even if faced with a multitude of enemies and it was inevitable that he’d get beaten to a pulp, of courageously chasing back fear. Because he was a man who had been initiated into the world of boxing by none other than a European heavyweight champion. He was a man who wouldn’t let anyone kick him around, much less his wife. If anything, he’d be the one to kick her around. Toe kick—that’s what I was always afraid he would do to her when he came home—and heel stomp.

One September morning, in order to put my mind at rest, I decided to calmly map out all the times my father had definitely hit my mother.

At first the prospect seemed complex and loaded with details but when I subjected each of the recollected images—a slap, a dish of pasta hurled at the wall, a scream, a glare—to the rigors of prose and articulated them into an organized series of events, memory started to waver and with some alarm I realized that I was left with only two irrefutable episodes.

The first one dated back to 1955, at some point between the fourth and fifteenth of June, the period of time during which my father exhibited twenty-eight of his works of art, including paintings, watercolors, and drawings, at the San Carlo art gallery, located at number 7 in the Galleria Umberto I arcade.

I sought out an image to begin. I envisioned him in bed, their big double bed. I had just brought him coffee and its aroma wafted through the house. He sipped it and read out loud to my mother, brothers, and me from the newspaper reviews that mentioned his name. Now those were the days . . . He always liked recalling those days. Waking up like that, the smell of sleep mixing with that of coffee, the first of an endless number of cigarettes, and the scent of fresh newsprint, anxiously scouring the pages and headlines and columns, and then finding his name—selftaught, no formal training, no art school, no pulling of strings— in print in the city papers or even the provincial ones, followed by a couple hundred of words about his work. See what he had managed to do, him, a man born on Barrettari alley, a man who had been forced by his father, a lathe worker with absolutely no understanding of art, to leave school and get a job. What a waste of youth. By the age of eighteen, in 1935, he was working for the railroad as an electrical repairman. Thanks only to his great intelligence and desire to improve his situation, by 1940 he was already second in charge. Now, as of a few years—it was 1951 at the time—he had become senior station master and train dispatcher for all moving cars on the lines in and around Naples. Now that’s satisfaction. An important job. And all because of merit, not thanks to seniority or favors. At the time he had been the youngest station master in all of Italy, word of honor, and much appreciated by his superiors, even if, it’s true, he did everything he could to get out of work and stay home and do his real job, the one he had been born to do: paint and draw, or as he said, pittare. Sure, a fair number of his colleagues couldn’t stand him; they called him a presumptuous shitty artist and accused him of being lazy, arrogant, and a blowhard. It’s true, he was lazy. He was arrogant. He was a blowhard. He was all those things, and the first to admit it. He felt he had the right to be lazy, arrogant, and a blowhard—to anyone who busted his balls. He was born to be a painter, not a railroader. But since he was the kind of person who did everything to the hilt, particularly if it offered him the chance to demonstrate that he could do it better than someone else, I believe that he did his job pretty well. Despite all the other ideas that floated around his head, one thing was for certain. When he was on duty—and he was on duty a lot, he had long hours, day shifts and night ones, and I remember because sometimes when I was older I’d stop by his office and watch him direct the traffic of convoy cars, chase them down, smack his ruler, triangle, and pencil on a huge drawing table in a way that was both petulant and extremely lucid—there were never any train wrecks or deaths.

Of course he took full advantage of his role. As senior station master he was authorized—he emphasized the fact that he held authority with great pleasure—to conduct random inspections of the stations in his jurisdiction four times a month. So, between 1954 and 1955, he inspected Cassino, Cancello, Ilva, and the Napoli Smistamento depot. He didn’t do it because he enjoyed inspecting: cocky fellow that he was, obsessed only with outshining everyone, the last thing on his mind was the actual inspection. Unless, of course, Federí went on to explain, he encountered an employee who was rude to him and led him to believe that he didn’t give a fuck about his role, his opinions, or his artistic endeavors, well then, he could just go straight to hell, and suddenly Federí became extremely meticulous. But otherwise, no. He took advantage of being able to inspect all those stations in order to catch the light and colors of real life in either pastels or tempera.

Because, although he was a railroader, he thought about nothing but the exhibition he was preparing. And indeed, when he was good and ready, he came home, shut himself in, told the station that he had rheumatic fever, gastritis, or any number of other ailments, and spent his time painting line signals, junctions, sidetracks, cattle cars, railyards, depots, and railheads. I remember each and every one of his paintings: my grandmother, brothers, and I slept in the same room where he painted, the dining room, where his monumental easel stood surrounded by his paintbox and canvases. I used to fall asleep staring at those visions, they seemed beautiful to me; I wish I could find them.

Between work and bouts of new illnesses, he completed a further series of paintings devoted to what he saw from the window: the surrounding countryside, but not the one that smelled of mint where I used to play as a kid with my brothers and friends, no; the one of felled trees and severed ancient roots, the flattened one, which by the end of 1954 was rapidly being transformed into a building site. He did studies of wastelands, pile drivers, cement mixers, bulldozers, hoists, storage silos for cement, a detailed rendering of the massacre of a hillside, and a painting crowded with scenes from a construction yard entitled Cantiere ’54.

Then he went on to still-lifes: he drew bowls we had at home and either a few dried herring or a couple of apples, a hatchet or a bunch of artichokes, a few mussels or some flowers, whatever he found lying around the house. He added two nudes to the group that he had done years earlier when he took classes at the Scuola libera del nudo, one done in sanguine and the other in charcoal. He even included a portrait of my brother when he had nephritis, which came out better, he said, than anything by Battistello Caracciolo. And that was it.

All that work took him eight months. The whole apartment on Via Vincenzo Gemito smelled of paint and turpentine. Every piece of furniture in the room we referred to as the dining room had been shoved up against the wall (how hard my mother had worked to obtain those pieces of furniture, and how carelessly he treated them) and at night there were always canvases drying on our beds. His wife complained, my grandmother grumbled. How could he let his children—meaning me and my three brothers—breathe that poison night and day? Had he forgotten that we slept in there? Padreterno, he’d holler, tell me what I’ve done to deserve a life of ball-busting by these two idiotic women. But then it was over: the task had been completed. I have no idea where he found the money to pay for the exhibition. The fact is that with a little help from Don Luigino Campanile, a shoemaker with a shop in Vomero but also an art-lover, who kindly offered to transport all the artwork in his delivery van, Federí went and hung his paintings on the walls of the San Carlo gallery.

__________________________________

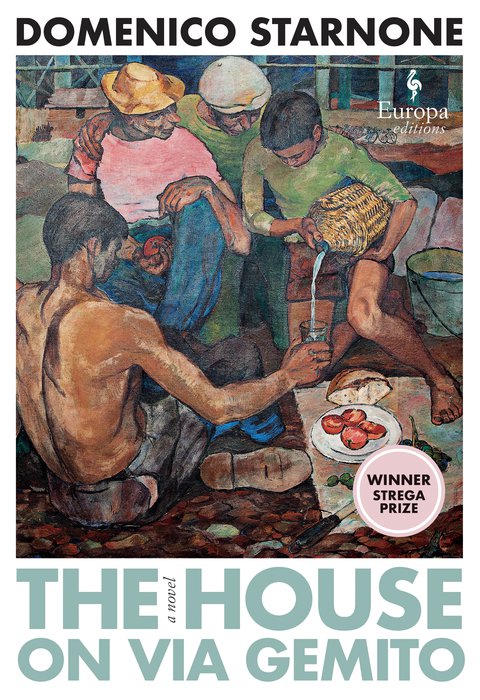

From The House on Via Gemito by Domenico Starnone (translated by Oonagh Stransky). Used with permission of the publisher, Europa Editions. Translation copyright © 2023 by Oonagh Stransky.